Hypocrisy and human rights, hate speech, and the surprising role of young people and their social media in the world historic changes occurring in North Africa and the Middle East have been our issues of the week at DC. While I know, from my ability to track levels of readership, each of the posts attracted more or less an equal degree of our readers’ attention, it was hate speech that stimulated an interesting discussion, interesting on its own terms, but also in the way it sheds light on the other posts of the week.

Hypocrisy and human rights, hate speech, and the surprising role of young people and their social media in the world historic changes occurring in North Africa and the Middle East have been our issues of the week at DC. While I know, from my ability to track levels of readership, each of the posts attracted more or less an equal degree of our readers’ attention, it was hate speech that stimulated an interesting discussion, interesting on its own terms, but also in the way it sheds light on the other posts of the week.

Gary Alan Fine is not worried about hate speech. Most of us are. He thinks it excites and draws attention, and that its negative effects are overdrawn. Iris “hates hate speech,” but thinks that we have to learn to live with it. It is the price we pay for living in a democracy. Rafael offers a comparative cultural approach, agreeing that in English hate speech may not be as pernicious as it may first seem. But he, nonetheless, reminds us that sometimes hate and its speech have horrific consequences, citing the case of a local preacher “insisting on an idea of building a memorial reminding folk that Mathew Sheppard is now in hell.” Rafael underscores that sometimes hate speech and aggressive actions are intimately connected, sometimes, even, hate speech functions as an action. Esther looks at the problem from a slightly different angle. She thinks that concern about civil discourse is a good idea, but asks: “shouldn’t we be thinking, talking and doing some more about cause and prevention of violent outbursts by lost individuals?” While, Michael is more directly concerned with hate speech and action, maintaining that it undermines democratic culture. “Hate frequently destroys the cultural underpinnings needed for democratic processes to emerge and thrive.” He then expresses his concern about the hate speech in Madison, echoing those who were most concerned with the relationship between hate speech and the massacre in Tucson.

© Akiramenai | Wikimedia Commons

And then, in a sense, the Supreme Court joined our discussion, supporting the free speech of anti-gay zealots at funerals, deciding more or less on Fine’s side of the debate. But, this was a legal position, not really deciding our political problem. How to judge hate speech? How to respond to it?

I don’t think there is an easy answer to these questions. But I think that the beginning of the answer is to be found in thinking about our practice here at DC. Look at the issue from different angles. Observe how various principles apply in different situations. Debate the issue. Act upon the implications of the debate.

Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi © Martin H. | Wikimedia Commons

Don’t support hate speech and its actions, or make believe that such thought and action is normal, as many have responded to Colonel Qaddafi over the years. Certainly don’t endorse a country’s participation and even leadership in a UN body on human rights when its leader spews hate and supports terrorism connected to that hate.

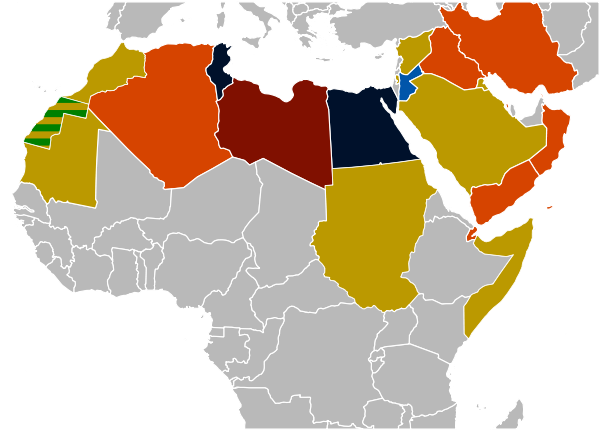

But do support the development of a political system which can be open to what Fine calls “lusty talk.” He maintains that “The allegiance to debate reflects the principles of the Founders, it doesn’t deny them. Being engaged in left or right disruption – talk or action – can be handled by a confident society. Yes, legislators, justices, and government officials must find grounds for reaching agreement, but they can do this – and over centuries have done this – within a welter of voices.” But of course, constituting such a confident (democratic) society is very difficult. Something we should note as we observe the revolutionary changes in North Africa and the Middle East.

© Unknown| Wikimedia Commons

Benoit Challand in his two posts examined how the counter power of civil society, with people acting independently and freely, has been the force behind the great ongoing transformation in Tunisia, Egypt and beyond. Not the magic of class identity or of sacralized politics, but youth, he tells us. I think what is particularly important is that the youth are basing their actions on free and civil discussion. Once a civil order is established, perhaps, it will be able to handle hate speech. But civility and its order must be supported as a top priority. It’s a precondition for democratic life, as we see it also is a cause promoting democracy’s institutionalization. And, I think, this is not only for newly constituted democratic societies. I should add: exactly these are the issues that I tried to work on in Civility and Subversion, one in which I consider not only civil intellectuals such as Walter Lippmann and John Dewey, but also subversive ones who sometimes use a language of hate such as Malcolm X.

Leave a Reply